Anne and Charlotte, side by side, in The Gun Group Portrait.

Very few readers – sometimes, even those who consider Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights cherished favorites – are familiar with the work of Anne Brontë.

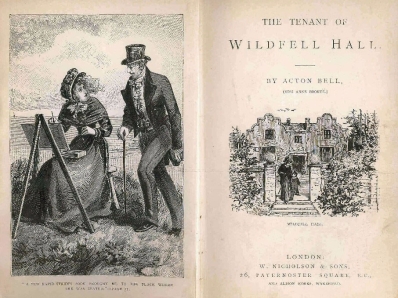

Looking back to when the Brontë sisters first published their works, Anne’s Agnes Grey and then The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was only budding in popularity until readership plateaued out altogether. Her work is rarely read anymore today, often catching readers of Charlotte and Emily by surprise to know there was a third sister – let alone that she published writing. The popular understanding behind this, even among many Brontë enthusiasts, is that Anne Brontë is the least famous of the three sisters because her writing was not iconic. Or sensational. Or “shocking” enough. No brooding antiheroes, no ghosts or fantastic elements.

However, the truth behind the reason Anne is barely a whisper in our world is thanks to Charlotte playing God. Anne Brontë’s writing, in fact, was well on its way to becoming all the rage in London and prestigious literary circles of the time.

But so was Charlotte’s work; her readership, along with (in an unlikely twist) Anne’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, had grown tremendously by 1850, after her sisters were already dead. It is very likely that Charlotte aimed to subdue Anne’s fame in light of her own new novels that she continued to publish (and in truth were hidden in the shadow of her beloved debut Jane Eyre). Alas, it is none other than Charlotte who actively prevented her sister’s work from achieving its full, deserved fame.

And there are a variety of reasons for why this could have been so. There’s little debate that upon looking closer at Charlotte’s relationship with Anne throughout their childhood and writing careers, there is some distaste and tension not to be ignored – Charlotte’s diary entry commenting on Anne’s writing as “a sweet and sincere pathos of its own” cannot be passed up only as patronizing when this is one of the only mentions Anne ever receives in her sister’s highly detailed diary. It’s curious to note they were not very close at all despite growing up together and sharing similar experiences. It does reveal these two sisters processed things very differently. They held very different value systems, and it’s apparent in how their writing endeavors played out.

1.) First and foremost – The Tenant of Wildfell Hall was, in some respects, a criticism of Jane Eyre.

In building Mr. Rochester’s character, Charlotte romanticizes the Byronic hero, a popular figment of Victorian literature – a brooding, secretive male character that is doomed to recklessness, violence, and tragedy. Only when disregarding the Jane Eyre’s sexual frustration that clouded her judgment of Rochester can readers objectively observe his character. Rochester is very clearly a sarcastic, controlling man, both indulgent and drawn to indulgent company. Over time, his character is revealed not only to have committed polygamy (following a history of polyamorous connections), but also to have neglected his wife suffering from mental illness. The way Charlotte painted him, however, made him appear more like someone simply driven into unfortunate circumstances, unwillingly tied to reckless family and company and forced to marry his wife. And that’s why he could be redeemed, Charlotte argued. That’s why Jane’s pious, ever-questioning, self-restrained personality was enough to inspire Mr. Rochester to change his ways for good.

That’s where Mr. Rochester’s character borders on unrealistic.

And this is where The Tenant of Wildfell Hall comes in. Anne allows a somewhat similar introduction to the novel’s protagonist, Helen Graham, as with Charlotte’s Jane Eyre; Helen is a pious, inexperienced woman with no intention of looking for a man. In an unexpected turn of events, she’s instantly charmed by a reckless and brooding obscure family friend (in this case, Arthur Huntingdon). Just like Jane, she receives warning after warning from everyone around her that she’s setting herself up for a risky marriage. But she shoots them down, reassuring both others and herself that yes, her husband has some warning signs, but she can fix him once they’re married. He can be redeemed.

Of course, that goes south. When someone has consistently been following a pattern of behavior their whole life, by no means will they quickly or easily “get fixed”, if at all. Arthur degenerates into alcoholism and infidelity a few years into being sick of Helen coaxing him out of his habits. He eventually neglects his wife and abuses his child, placing them both under house arrest and withholding any resources they might use to run away. Soon enough, Helen comes up with an elaborate secret plan with the help of the good housekeeper to escape town without a trace – set up a new identity – start all over again. She dedicates her time to raise her son to be everything her husband was not. In other words, she raises him to be the opposite of a Byronic hero.

There were critics that drew parallels between Mr. Rochester and Mr. Huntingdon. Charlotte passionately deny this in a highly defensive letter to a critic, retorting “You say Mr. Huntingdon reminds of you Rochester. Does he? Yet there is no likeness between the two.” But she would still not be able to deny the parallels between the setup of her own novel and Anne’s. The only difference between the two works, really, would be that while Jane Eyre detailed the romance between the Byronic hero and his savior-heroine, The Tenant focused on their dynamic once they were committed to marriage.

Anne Brontë was debunking what she perceived to be delusional Gothic romance.

And while doing so, she dealt with revolutionary themes like alcoholism, toxic masculinity, and the empowerment of single working mothers. Of course nineteenth-century literary critics were stunned by this work that would fit far better in a more modern society.

2.) Charlotte saw Anne’s ideas expressed in her writing as too revolutionary, feminist to a fault – potentially tainting or scarring the Brontës’ carefully cultivated reputation.

After all, the sisters had taken great pains to publish their work under androgynous pseudonyms, hoping to avoid sexist critiques from their male peers. There was a conflict with the rampant conspiracy theories that the “Bell brothers” were all just one author, and that the three separate names were a method for garnering more attention. This pressured the Brontës’ publishers to threaten to cease supporting their work.

Charlotte and Anne themselves had had to take the major risk of traveling to London and meet their publishers to prove their separate identities. This also meant they would potentially lose all credibility in revealing they were, in fact, female. The publishers, needless to say, did find out the now-famous Bell brothers were really the Brontë sisters. But in a happy twist, they promised to keep their identities secret. In fact, Charlotte’s publisher George Smith turned out to be perhaps her biggest fan, asking if he might introduce her to his Jane Eyre-obsessed family – even taking her out to famous sights and shows in London.

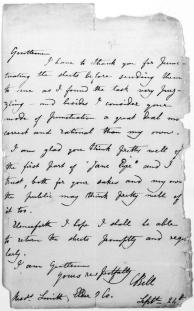

So when The Tenant received heavy criticism for its incredibly challenging themes, Anne was not too concerned with public opinion potentially endangering her career. She chose, instead, to address criticism head-on in subsequent editions. She kept her novel’s introduction simple, honest, and to the point:

“I find myself censured for depicting con amore, with ‘a morbid love of the coarse, if not of the brutal’, those scenes which, I will venture to say, have not been more painful for the most fastidious of my critics to read than they were for me to describe. I may have gone too far; in which case I shall be careful not to trouble myself or my readers in the same way again; but when we have to do with vice and vicious characters, I maintain it is better to depict them as they really are than as they would wish to appear….I am satisfied that if a book is a good one, it is so whatever the sex of the author may be. All novels are or should be written for both men and women to read, and I am at a loss to conceive how a man should permit himself to write anything that would be really disgraceful to a woman, or why a woman should be censured for writing anything that would be proper and becoming for a man.”

But Charlotte was not about to toy with the unlikely, perfect turnout of events of the Bells’ writing garnering uninterrupted fame.

Upon The Tenant being requested another edition a year after Anne’s death, Charlotte was determined to suppress the book’s republication. She even made it her dying wish. She was not subtle about hiding her hate for The Tenant while her sister was alive, even contacting Anne’s literary editor W. S. Williams at Smith, Elder & Co.:

“The Tenant of Wildfell Hall by Acton Bell, had likewise an unfavourable reception. At this I cannot wonder. It hardly seems to me desirable to preserve. The choice of subject was an entire mistake. Nothing less congruous with the writer’s nature could be conceived. The motives which dictated this choice were pure, but, I think, slightly morbid…. [She was of] naturally a sensitive, reserved, and dejected nature; [the terrible effects of talents misused and faculties abused] sank very deeply into her mind; it did her harm. She brooded over it till she believed it to be a duty to reproduce every detail (of course with fictitious characters, incidents, and situations) as a warning to others. She hated her work, but would pursue it…. She was a very sincere and practical Christian, but the tinge of religious melancholy communicated a sad shade to her brief, blameless life.”

It is clear that Charlotte wrote off Anne’s (for the times) radical insight into alcoholism and abusive marriage. But Anne, in fact, had an educated understanding of both of these topics. She watched her brother Branwell’s degeneration in alcoholism, beginning with his indulgent friends and brooding personality all the way to polyamorous connections and frightening tantrums and episodes. Anne was close to her father, too, who would relay to her stories about the townspeople that reached out to him for help – like that of Mrs. Collins, who he was helping to escape from her abusive, alcoholic husband.

And in her highly autobiographical work, Agnes Grey, Anne wrote about her struggle as the youngest sibling in being taken seriously or being trusted to have thick skin. Like her novel’s titular character, Anne did go on to prove her independence and thick skin when she took on more responsibilities than she was ever expected to. She first took Emily’s place in the Roe Head School. Whereas Emily had dropped out from homesickness, Anne was ready to seize her window of opportunity and, through declining health, finished her education. When financial situations in the Parsonage grew rocky, Anne set out to find a stable job as a governess (even when her family urged her not to). Ultimately, it was Anne that stayed in her job the longest, between the sisters, despite the terrible abuses she suffered from her employers.

She had rich tales to tell from her perfectly sound mind.

Contrary to Charlotte accusing Anne of being disturbed by dramatic stories, and of choosing to write on topics she knew nothing about.

Ultimately, it’s true that Anne did not receive very much reception on her work at all during her lifetime. More of it was coming in after her death, until Charlotte stemmed the growing popularity. But the reactions that did come about her work (even some that managed to trickle in decades after the Brontës’ lifetime) reveal her critics’ shock and amazement at the way she dealt with her subject matter. Anne clearly made an impact on her readers. She covered a greater array of daring themes with arguably more consistency and seriousness than her sister did. She was well on her way to become the most infamous, most discussed author among literary circles. Charlotte, herself, could not deny this.

But she feared for her reputation and would do anything to protect it. She would blame the scandalous nature of Anne’s work on her naivety, convince her publishers Anne was not a headstrong, defiant person like her work suggested. And so today, we don’t remember Anne as a revolutionary writer. If we have heard her name, we don’t associate it with her strong voice.

These aspects show perfect motive for Charlotte taking her sister’s image into her own hands.

Never having gotten along well as siblings, interestingly different value systems, evident tensions when it came to writing – the beloved author of Jane Eyre wouldn’t be ready to share the spotlight with her little sister. Clearly, Anne’s style of writing and subject matter was not the reason behind her fading legacy. It is simply illogical to think that when considering the iconic, the sensational, the shocking quality of The Tenant and the intense (though few) reviews that were received.

While Charlotte was known for her incredibly soft-spoken nature being stark in contrast to her strong voice in writing, Anne is not nearly as lucky. If she is recognized as being a Brontë sister at all, she is largely remembered only for her gentle whispers – but almost never for her words that were equally poignant, if not more so, than her ever-celebrated sisters.

All information is drawn from The Life of Charlotte Brontë by Elizabeth Gaskell, The Brontës by Juliet Barker, and the Brontë Parsonage Museum.

Leave a comment