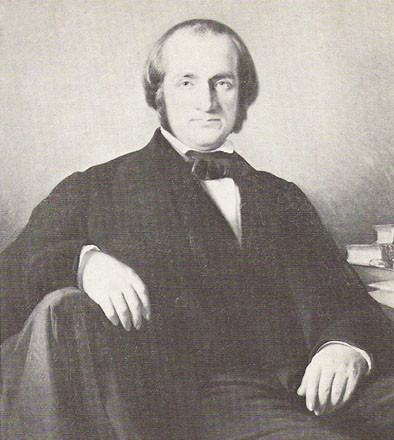

Pictured above: Professor Monsieur Constantin Héger, love interest of Charlotte Brontë.

“Monsieur, the poor do not need a great deal to live on — they ask only the crumbs of bread which fall from the rich man’s table — but if they are refused these crumbs — they die of hunger — No more do I need a great deal of affection from those I love — I would not know what to do with a whole and complete friendship — I am not accustomed to it — but you showed a little interest in me in days gone by when I was your pupil in Brussels — and I cling to the preservation of this little interest — I cling to it as I would cling on to life.” – Charlotte Brontë

The powerful voice that would soon publish Jane Eyre to be all the rage in Britain had—just like you and me—succumbed to the cringe-y behavior that comes with doomed romantic feelings. One of the greatest figures of Victorian English literature went through the painfully awkward experience of one-sided love. It was an event that was off-limits for discussion during her life. Out of respect, her friend and biographer Elizabeth Gaskell omitted all mentions of the fact Charlotte had obsessive feelings for her former instructor and employer.

The winter of 1841 came with some disappointments when Charlotte was ready to be done with her work as a governess.

Her sisters were equally as eager in finding another opportunity in place of the job they despised; the three of them formulated a plan to open their own Sunday school near their home. Their Aunt Elizabeth was even on board with this goal, ready with funds when hopes were quickly dashed. Branwell was facing trouble as railway clerk at Sowerby Bridge, disappointing his employers by day and drinking by night. His alcoholism had reached the ears of Haworth—he was becoming all the talk of the town. No one in the community would be willing to send their children to a Sunday school owned by the Brontës.

While Anne resolved to continue working as a governess, Charlotte and Emily, though adamant never to return to the job, were still forced to find another occupation.

By early 1842, Aunt Elizabeth put the failed-Sunday-school funds to further Charlotte and Emily’s education. Rev. Brontë had heard from a pastor based in Brussels, Belgium, of the reputable institution Pensionnat Heger—perhaps another hope for improving his daughters’ resumes so that they might find work with better employers.

Travelling across an ocean, hearing multiple languages murmured in livelier crowds left her starry-eyed.

Having been held down by her family, constrained within the limits of her small, conservative town had done much to Charlotte’s morale. This significant transition was something of an awakening for her, and it is clearly the earliest part of Charlotte’s romance. It’s something consistent in both autobiographical pieces Jane Eyre and Villette. The cloudy, dark carriage or ship rides, the nervous exchanges with strangers in transit, and finally the early morning arrival at the doorsteps of the protagonists’ new charges tell us a bit of how Charlotte felt during her journey to the Pensionnat.

Monsieur Heger’s personality was a fine complement to the shocking nature of Brussels. He most notably taught French and German, known not only for the unconventional Socratic structure of his lessons but also for his abrupt nature that often set many of his students in tears. He was full of ideas and perspectives that Charlotte had never considered before. While her first French lessons were some of her strangest, in terms of her own interactions with Professor Heger—echoed in Jane’s first meeting with Rochester after injuring himself on ice, and in Lucy Snowe looking on as her peers sobbed at the wrath of Monsieur Emmanuel—she was awakened to a new kind of personality. Jane Eyre, having been hidden away in the tiny Lowood School for most of her life, had an “otherworldly” look to her as she and Mr. Rochester chipped away at their contrasting worldviews in their battle of wits. Professor Heger, too, was melting the ice Charlotte brought with her from the chilly moors.

Mr. Rochester is a fresher, but also likely more idealized memory of Constantin Heger.

Charlotte, as a writer, does not leave any doubts in the minds of her readers as to why Jane would have fallen in love with him. They are friendly with each other and intellectually in sync. Jane and Rochester quite clearly always look out for one another – as Charlotte and Heger likely did as well in her memory of him by 1846. Just a few years ago, in 1844, had she returned home depressed, having quit her job for reasons still unclear. Upon returning home, she still could not help but write her Monsieur Heger the pained love letters known today as the collection of Heger Letters. Writing Jane Eyre was certainly a coping mechanism for Charlotte dealing with her doomed feelings that became known, by then, to the yet indifferent Heger himself. Her charming portrayal of Rochester called for readers to sympathize with him, fall in love with him like Jane. Charlotte still loved Heger.

But Monsieur Emmanuel of Villette is not as forgiving.

At this point, Charlotte was looking back on her Brussels era six years later—after she lost all of her siblings and after her future husband Rev. Nicholls had become a significant part of her life. She clearly was bitter not only about Heger, whom she had rather turned into a caricature as Emmanuel, but also of the character of Brussels altogether that she represented in the fictional town of ‘Labassecour’ in her novel (French for farmyard). Readers don’t fall in love with Monsieur Paul, let alone connect well at all with protagonist Lucy Snowe.

Charlotte’s previously fiery feelings had cooled to an entirely different tone. Villette is terribly dry. It’s not nostalgic, not pleasant in the slightest. It’s as though the writer of the rosier Jane Eyre had made a major a change in her worldview and reached new realizations. She had a newer and harsher perspective on her past.

So what exactly had happened between Charlotte and Constantin Heger? What prompted young, hopeful Jane to turn into the older and icier Lucy Snowe – to transform the romantic Thornfield Hall into a farmyard?

Stay tuned for Part II to examine Charlotte Brontë’s Brussels era in closer detail.

Leave a comment